Island 40: Finale on Finnhamn, Stockholm Archipelago / Stockholms skärgård

I boarded the ferry from Vaxholm with mixed feelings. Excitement that I was about to reach my 40th island. A small sense of sorrow that my year-long adventure was coming to a close.

Finnhamn thankfully rolled the red carpet out for me – well, metaphorically at least. Stepping off the ferry clutching a hot coffee and pastry onto a sunlit but very quiet island quayside I was immediately greeted by the arrival of two White Tailed Eagles, soaring low over the sound between Finnhamn and her sister islands. I couldn’t have asked for a better finale fanfare.

Like Grinda, my Island 38, Finnhamn was all the better for management by the Archipelago Foundation. Likewise Finnhamn in late April is also an island reawakening, preparing to greet the much larger number of summer visitors, who are drawn to the outer archipelago by the crisp air, cool swimming waters, woodland trails, and wildlife. As well as places to stay, kick back, relax, eat, drink and be merry (although, except the year-round hostel, everything was closed during my visit – hence disembarking well prepared with my own elevenses).

Finnhamn topographically is actually three conjoined islands – Stora Jolpan, Lilla Jolpan and Idholmen – with one attached small islet that hosts the main quay. But it also lends its name to the immediate archipelago within the Stockholm archipelago. The main island group of Finnhamn qualifies as a single island because it functions as one. Through the passage of time, these rugged Precambrian granite isles have become naturally attached, with the sounds between them having silted up.

A good potted history of the island can be found here. In short this group of islands owes the name ‘Finnhamn’ to the development of a Finnish trading port here. Later, in the early 20th century a coal merchant built his summer manor on the island. By he mid 20th century the island had been purchased by the City of Stockholm as a leisure retreat, with the island finally being handed over to the Skärgårdsstiftelsen in 1988.

A consequence of Skärgårdsstiftelsen’s management is the presence of well-signed nature trails, and work underway to improve the unique oak woodland habitats. They have also reintroduced traditional farming through the establishment of the small organic farm on Idholmen.

Finnham had all the hallmarks of what I most enjoy in an island. Small enough to walk around in a day, rugged yet welcoming, away from the crowds whilst bustling with wildlife, and a meandering coastline that only nature could have drawn. Finnhamn was a truly fitting finishing line of my forty islands adventure.

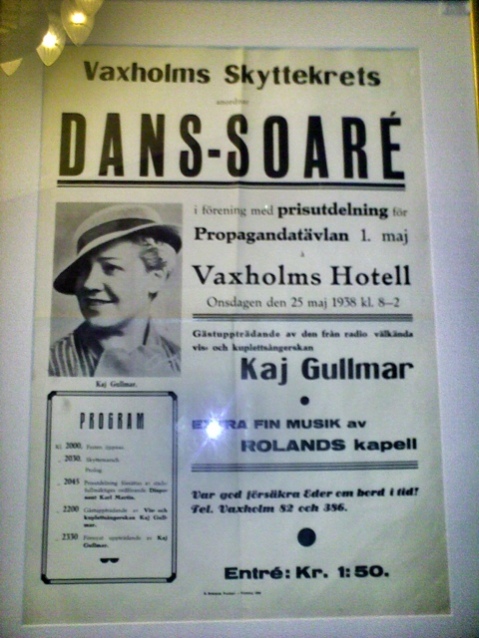

Island 39: Vaxholm, Stockholm Archipelago

Towards the middle of the intertwining sounds and bays of Stockholm’s archipelago sits the island of Vaxholm. In fact the island and the town of Vaxholm are synonymous. Today a commuter-come-day-trip resort, and the capital of the archipelago, this island was occupied at least as far back as the Viking period.

Yet this place owes most of its character and personality to the need for a defensive outpost for Stockholm in the 16th century. Eventually Vaxholm was transformed from a garrison town and customs post into a place of leisure and recreation. Well-to-do Stockholmers of the 19th and 20th century came to Vaxholm as a place of entertainment and summer escape, and the large modern harbour, and regular ferry service to Stockholm, means it remains a summer playground today.

From a view across to the Vaxholm Fortress on its own fortified island, to the old wooden buildings in the small historic centre, Vaxholm in Spring is low-key but lovely place. The real bustle and activity is on the harbour-front with ferries and yachts to-ing and fro-ing, overlooked by cafes and restaurants and the Waxholms Hotell. Indeed the hotel itself, where I was fortunate to stay, with a Scandinavian take on Art Noveau, adds to the nautical and resort-like feel of the island. The hotel interiors are reminiscent of an ocean liner, with the restaurant feeling like the bridge of a ship, looking out across the harbour and towards the Fortress, watching over the boat traffic between the surrounding islands.

Arriving on the quay mid-evening from Grinda, it was literally only a few steps to the Waxholms Hotell and a tasty dinner of fried Baltic herrings, lingon berries and mash potatoes. A welcome treat after a long day of travel and visiting Island 38: Grinda.

An hour by ferry, but a world away from Stockholm, Vaxholm’s a great base for touring the central archipelago. It is also worthy exploring itself, with some fine old wooden buildings and narrow streets in the heart of the modest but lovely town centre.

Island 38: Grinda, Stockholm Archipelago / Stockholms Skärgård

Above:blåsippa adorn the woodland floor of Grinda in Spring.

For an island-bagger, Sweden is perplexing.

According to Sweden’s state statistical agency there are 223,881 islands in Sweden’s territory. Of these 98,372 are located in the sea, with the remainder being in lakes.

For my forty islands I’m only interested in islands in oceans and seas. So 98,372 amounts to 2,468 years worth of 40 island challenges.

But if I limit this further, to exclude islets of 1 hectare or less – which accounts for about 90% of Sweden’s islands – then this drops down to a much more manageable 9837 islands, or circa 247 years worth.

Thankfully I managed to narrow down my choice a little more by choosing to go to the Stockholm archipelago. This means I only had 24,000 islands and islets, which by applying the 90% rule, gave a ballpark of c. 2,400 proper islands. Or, to put it another way, around 60 years worth of 40 island challenges to choose from.

In reality the selection process was much easier than this. The practicalities of Waxholmsbolaget and Cinderalla Boats early spring timetable (which although extensive, are not nearly as frequent as in Summer), and the desire to spend a good amount of time on each island visit, significantly narrowed my options.

So there I was. I’d arrived on the Stockholm quayside close to lunchtime on Friday. The only fixture in my day was a requirement to get to my hotel booked on Island 39 (Vaxholm, the hub of the central archipelago boat routes) by nightfall. A quick scan through the maps and timetables ensued. Island 38 jumped of the page. Grinda.

Grinda is situated towards the centre of the Stockholm archipelago, but one of the first islands you meet with very extensive public access. This comes by merit of ownership by the very wonderful Archipelago Foundation, an organisation set up with the express aim of conserving the special nature and culture of islands across the archipelago. Grinda’s 172 hectares

provide a cross-section of Baltic landscapes, ranging from a beautiful nature trail through the wilder, pine-forested, part of the island, areas more recently returned to traditional farming, and the more populated part which accommodates the island’s guest pier, hotel (built in the Art Nouveau style by Henrik Santesson, the Nobel Foundation’s first director – and a former owner of Grinda), hostel and summer holiday cabins.

Grinda, blessed by the warmth of the late April sun, was very much a place reawakening after a winter’s hibernation. Nature was bursting gently into bloom, birdlife – on land and sea – was getting into full swing. Likewise work was well underway by the Archipelago Foundation and Grinda hotel and hostel staff to welcome the greater number of visitors that come in the main visiting season from May to September. In many ways I felt like I had the island to myself, being one of only a handful disembarking from the ferry at lunchtime, and then departing just as a boatload of guests arrived for an evening’s entertainment at the hotel and waterside bar.

Sitting on the summit of flat glacier-smoothed rocks towards the east side of the island, overlooking the panorama of adjacent islands across the sound, with nothing but the late afternoon sun, clear breeze, birdsong, and lapping Baltic Sea as companions, is one of those experiences that it’s hard to beat. As an introduction to the archipelago, it certainly could not have been bettered.

Island 37: Mallorca

The Mallorcan spring brings a splash of colour to the island making it feel like a land of plenty. With clear cool seas, verdant pastures, birdsong, wildflower meadows, a warming sun and heavily laden orange and lemon groves this all feels like an island showing off a little before being overtaken by the millions who visit each summer.

Mallorca, as the Mediteranean’s seventh largest island does variety very well. The Tramuntana mountains, whilst never very high, do a good line in rugged and spectacular, with sea cliffs plunging into holiday brochure seas. The citrus groves and small towns of Biniaraix and Fornalutx in spring feel like a Meditteranean take on the Cotswolds – all stone-built farms, narrow lanes, villages and vistas.

Valldemossa, if you squint a bit, and let your imagination roam, feels a bit like an alpine village in summer (although that might have been the impact of seeing the backsides and swiss cross marked bikes of a good number of Swiss and German cyclists on a break with Max Hürzeler). Pollença feels like a historic town you might just encounter in the Dordorgne. Palma de Mallorca meanwhile is a magnificent city which has a hint of Barcelona, but with a harbour full of millionaires yachts and shopping boulevards giving it a twist of the resorts of the south of France. Ses Salines and the area of coast nearby, looking out to the Islas Cabrera could do a screen double for an Inspector Montelbano mystery.

Yet through all of this the island stays confusingly true to itself. Placenames vary from Catalan to Castillian depending which sign, map or guidebook you’re looking at. The cuisine serves up plenty of borrowed and blended specialities – I especially enjoyed the Mallorcan take on a Paella with spuds in the supporting role instead of rice. The local red wine is stunning but rarely seems to make it to these shores.

After a week of touring in the run-up to Easter, where the varied celebrations and festivals added their own to the sense of drama and theatre, I can say, hand on heart, two things:

1) I can’t think of many nicer places in Europe to spend some time in the Spring.

2) 37 islands into my 40 island journey, I think I could really get used to this island bagging lark!

From the archive: The Monach Isles, Outer Hebrides

Whilst I hatch plans for my final four of the forty, here’s a photo from a visit around five years ago to one of the least visited corners of the British Isles. My picture depicts an abandoned and crumbling house, on the abandoned archipelago of the Monach Isles, a place otherwise known as Heisker.

The Monach Isles sit off the west coast of the Outer Hebrides, a low group hunkered down against the roar and swell of the Atlantic Ocean. Further out sits the open ocean spectacle of the St Kilda archipelago. St Kilda’s islands and lofty sea stacks feel like they have chosen to defend themselves by donning armor and sheltering with shields. The Monach Isles feel like a much more fragile group, hanging on to their existence – and only just – by lying low and rolling with the punches of the tides and winds.

A useful potted history signals the sporadic and interim nature of settlement here, made hard by the constant storms assailing these islands. The Monachs were most recently abandoned on the retirement of the crofting MacDonald brothers in 1943 and the fuller history appears to have been punctuated with episodes of previous mini-booms and busts, rises and falls. For example the isles had a peak population in modern history of 135 souls in 1891, but only having recovered to this level as a consequence of resettlement following an earlier abandonment. There appear to have been earlier eras of reputed Monastic use, by both Monks (Monach is attributed to the word ‘Monk’) and Nuns, yet little physically remains to show for their endeavours. Further back into the folklore, there is also the tale of MacCrimmon. This holy man, who could perhaps have been another St Cuthbert of the early Christian church, sailed to the islands in search of solitude and meditation. The local fishermen from North Uist who took him there saw no sight nor sound of MacCrimmon ever again.

The hallmarks of the Norse influence, found elsewhere in the Hebrides, are signalled in placenames but little else physically signals this connection. Stretching yet further back it’s almost certain that there was prehistoric settlement, but any remains are ephemeral and elusive. A major shell midden was reported as discovered in the early 19th century. Like other recent visitors we saw remains (see below) very likely to be from similar middens, uncovered but alas also likely very quickly eroded in the ever shifting sands and shoreline. The whole of the island’s history feels like this. Eroded, silted over or blown away, but hanging on just enough to know it is still there.

Today the island, although in private ownership, serves as a National Nature Reserve, and is especially significant for the UK’s breeding population of seals, for breeding seabirds, and the flower rich machair. Scottish Natural Heritage have produced a very useful leaflet on the wildlife of the isles.

Human visitors are very few in number. Just a smattering of kayakers, alongside those arriving on their own vessel or on charter boat trips finding a calm window in the weather . There’s more about the limited opportunities to visit these somewhat forgotten isles here – http://www.monachs.com/. But if you do try to visit, make sure you sail and tread carefully.

Island 36: Jersey

Belatedly, here’s a few words on my Jersey visit over New Year 2011/12 – my fourth Channel Island within my target 40.

It was a fairly brief trip – three nights in all. The weather conspired against us. Not surprising for a winter island visit, though we didn’t let this get in the way of exploring. But, blimey, it was wet!

This brought its own atmosphere to the island. A raging winter sea, sea mists and a bracing wind bring their own delights. They also provide a solid excuse to scoff some amazing food, ranging from the comforts of an al fresco chip butty at the Hungry Man on Rozel’s quayside kiosk to spoiling ourselves to a Michelin starred dinner. St Brelade‘s, and L’Horizon where we stayed, are especially well placed for a temporary (or permanent) gourmand’s adventures.

The photo’s I hope say all that needs to be said about Jersey’s amazing coastal landscapes. I intend to return to enjoy them in the sun!

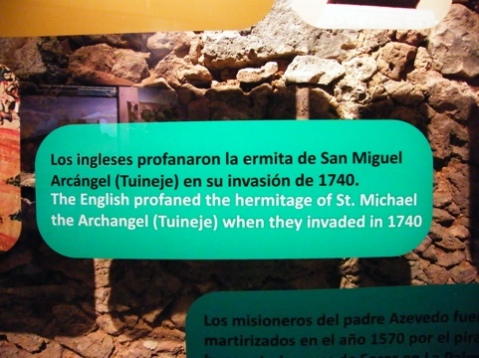

Island 35: Lanzarote

Lanzarote sits at the eastern end of the Canary Islands archipelago, close to the African continent, with the coast of Morocco a mere 80 miles away. Although perennially windy, early December’s a pleasant time for a Brit like myself to escape the late Autumn rain and cold of the British Isles for a reminder of summer. Although there’s not really any time of year when the Canaries are out of season, this is probably one of the quietest periods of year to visit, giving the island a very welcome calm and relaxed feel, allowing the Island to rise above the unfair “Lanzagrotty” caricature it often gets.

In my few days I managed to pack in some time in the capital Arrecife – a surprisingly pleasant and relaxed small city – as well as exploring the rest of the island.

I very much enjoyed the rough volcanic terrain found across much of the Island, most especially within the Timanfaya National Park.

The biggest surprise though was the positive imprint across Lanzarote of the architect Cesar Manrique, with his uber 60s and 70s style of design, fusing modernism, traditional Canarian architecture with a sensitivity to nature. He not only managed to apply this in his own designs, but also, to a degree, was successful in shaping the way in which Lanzarote’s holiday resorts grew, largely without high-rise hotels. The outcome beyond his own work is not always very beautiful (although it is often pleasant as attested to me in a couple of nights stay at a vast but quiet out of season Costa Calero), but it is much more appealing than perhaps other places I’ve visited that are so overwhelmingly dominated by a tourist economy.

Certainly Manrique’s intent was benevolent. After a few formative years in the hubbub of mid 1960s culture and creativity of New York, Manrique returned to his home island of Lanzarote with a singular vision:

“I came with the intention of turning my native island into one of the more beautiful places in the planet, due to the endless possibilities that Lanzarote had to offer. ”

This he largely achieved. Yet whilst Manrique’s memory may not fade, his influence may be waning. There’s a whiff of a potential for over-development and sprawl in a few places. Yet positively there are also hints of other forms of tourist development which make harmonious use of Lanzarote’s natural assets such as nature, sun, wind, surf, unique viticulture and landscapes.

The Longstone Lighthouse, Beacon of the Outer Farnes

The Longstone Lighthouse takes a place as an icon of heroism in Northumberland -and British – history. It was from this light that on 7th September 1838 a 22 year-old Grace Darling rowed with her lighthouse keeper father, to rescue survivors from the SS Forfarshire, which had run aground on Big Harcar Rock.

This picture shows the Longstone Lighthouse in the distance, seen from Staple Island. It is a piece of photo art built from a picture I took during a visit I made to the Farnes about five years ago. But you can find pictures from my most recent trip to Staple Island and Inner Farne in Summer 2011, here and here.

Still waters, hot mackerel

Above: “Two fishing vessels in Heimaey’s harbour, in the Vestmannaeyjar / Westmann Islands, Iceland.

A recent anthropological study on the potential impact of environmental change on fishing-dependent communities quotes a Vestmannaeyjar fisherman’s fear of the loss of fishing skills and traditions due to quotas:

“I used to know that when the sea and the weather got colder it would be easier to get haddock. And when the wind was from the south-east, making bad weather, it would be easier to get cod. In the Autumn, when the mountains over on the mainland began to look grey in the distance it would be easier to get haddock – these were the signs. But knowing these things is not so important these days, because now the government tell us where the fish are.”

Interestingly, this quote pre-dates the turmoil of the economic crisis in Iceland which spread out across Europe and the world (the research was published in 1997).

Woven on top of the economic pressures are further environmental and political changes. For example, we have seen recent signs of a shift north of fisheries for mackerel, as the fish start to seek colder waters, and the Vestmannaeyjar fishermen look for targets for their often newer and more advanced vessels.

This is perhaps good news for Iceland, but could set us back on course for strained relations between the Icelandic and UK (and Faroese & Norwegian) governments and fishermen.

With a devolved parliament in Scotland, and more at stake for Scottish fishermen and politicians, as well as tense discussions around Iceland’s entry to the EU (with the domestic and international tensions and trade-offs inherent in such circumstances) this could get increasingly difficult. Two pieces of reportage – Icelands mackerel fishery is legal and responsible say vessel owners and a recent press release from the Scottish government mackerel talks for 2012 underway show the opening salvos in a war of words (although Scottish fishermen have already carried out at least one mini blockade of a Faroe Islands vessel.). The memories of the Cod Wars remain raw for some.

So in my photo sit two boats, one blue, one red. The harbour is a picture of stillness. But a broader and bigger story continues to unfold.

From the archive: Farne Island Puffins at One O’Clock

Above: a small piece of photo art from my visit earlier this summer to Staple Island in Northumberland in the north of England. The island, managed as a nature reserve by the National Trust is home to around 80,000 puffins during the breeding season.

The original picture was a low resolution shot captured by mobile phone. It’s taken from my Instagram collection. More pictures from my visit are here.

You can read much more about the Farne Islands on the Head Warden’s Blog.